Looking into Pittsburgh’s Segregated Communities

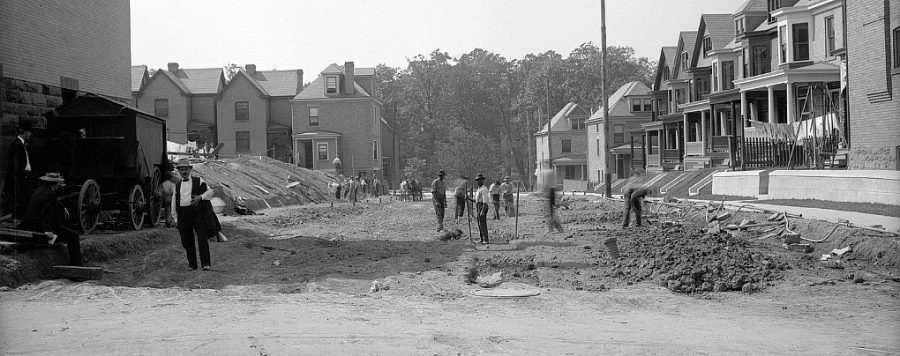

Picture of Pittsburgh neighborhood Point Breeze from many years ago.

Growing up at the junction of Point Breeze, Homewood, and Wilkinsburg Borough, the drastic differences between the three neighborhoods had always confused me. How was it that driving just three minutes north I would see businesses with barred windows, empty plots of land and dilapidated housing, but going in the opposite direction would bring newly paved sidewalks and houses with tidy green lawns? It isn’t hard to see that many of Pittsburgh’s communities still remain incredibly segregated even though it’s a city that prides itself on being stronger together.

Looking a little deeper into why Pittsburgh’s neighborhoods and communities still seem segregated it’s important to look at the local policies that have shaped our city over the years. Our communities are a product of their careful planning and execution but also their shortcomings and biases. Many housing policies of the early 1900s were specifically designed to be exclusionary and to keep our neighborhoods segregated.

For example in 1923 the city of Pittsburgh enacted its first citywide zoning ordinance, designing Pittsburgh’s neighborhoods by prescribing what type of housing could be built where. Throughout the years planners would update the ordinance further restricting what types of housing could be built in which zones, forming the start of a divided city.

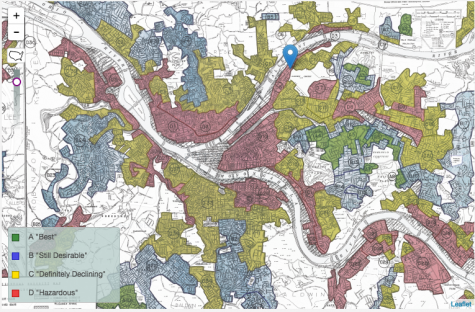

By the 30s, government surveyors started to grade cities across America, color coding them green for “best,” blue for “still desirable,” yellow for “definitely declining,” and red for “hazardous”. These ‘redlined’ areas were the ones that local lenders discounted as credit risk, largely because of the residents racial and ethnic demographics. Neighborhoods that were made up of predominantly African American, Jewish, or immigrants from Asia and southern Europe were deemed undesirable. Loans in these neighborhoods were unavailable or incredibly expensive, which made it increasingly harder for low-income minorities to buy homes, which is one of the many ways to accumulate wealth. For homeowners a monthly mortgage payment can act as a forced savings. As you pay down your principal you build equity, which helps increase net worth.

It’s no secret that these policies made their mark on America and still have a lasting, harmful impact on communities today even after the racist practice was banned over fifty years ago. Since the redlined communities were overtly denied opportunities to develop, it left those neighborhoods and residents falling behind other neighborhoods where businesses, schools and housing grew. According to a study done by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, 74% of the previously redlined neighborhoods are low-to-moderate income neighborhoods today, and 64% are home to predominantly minorities. “It’s as if some of these places had been trapped in the past locking neighborhoods into concentrated poverty” says Jason Richardson, the director of research at the NCRC, a consumer advocacy group.

But some of these neighborhoods didn’t start off of the wrong foot. Going back to the 1920s the Borough of Wilkinsburg was one of Pittsburgh’s most outstanding suburbs. Over the upcoming years Wilkinsburg was transformed from a wealthy, predominantly white community, into an area with a majority minority population and troubled with high crime. This change didn’t happen overnight. Gentrification, which made affordable housing impossible to find in some areas, along with the demolition of other black communities for commercial construction, led many black families pushed out of the city of Pittsburgh into the Borough of Wilkinsburg. As black families moved in, the white families left in droves. This left businesses and schools in the area at a great disadvantage. Some see Wilkinsburg’s plight as evidence of a broken school funding syst em that shortchanges children from poor families, while others see it as an argument for investing in charter schools instead of trying to turn around dysfunctional systems. One of the only high schools in the area, Wilkinsburg High School, has struggled the most, coming to the eventual decision for the school to close along with the only middle school in the area as well.

em that shortchanges children from poor families, while others see it as an argument for investing in charter schools instead of trying to turn around dysfunctional systems. One of the only high schools in the area, Wilkinsburg High School, has struggled the most, coming to the eventual decision for the school to close along with the only middle school in the area as well.

So what’s really being done to help desegregate our neighborhoods and communities? Well, in 1968 the Fair Housing Act was passed, prohibiting discrimination concerning the sale, rental, and financing of housing based on race, religion, national origin and sex. Though progress has been made, there are still extreme racial disparities among homeownership and wealth. Today the Black homeownership rate has not changed but white home ownership has increased.

But, by collecting data and establishing clear goals to determine what progress is being made, and by holding the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) accountable for enforcing fair housing policies we can grow towards a more integrated and fair future. Integrating schools promotes more equitable access to resources and can help reduce racial disparities in education. Clearly the impact of integration can go far deeper than simply ensuring that everyone has fair access to housing opportunities.

Zoe Obenza-Bridges is a senior at Pittsburgh Allderdice High School. At the school newspaper, The Foreword, she is the lifestyle editor and enjoys investigating...