Pittsburgh’s First Thanksgiving: Our Historic Contribution to the National Holiday

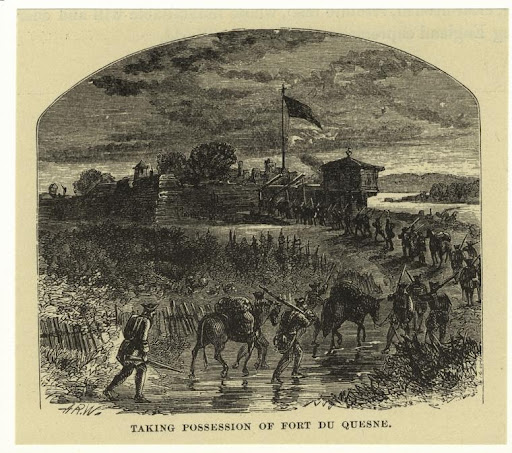

In November of 1758, British forces found the remains of Fort Duquesne in Pittsburgh.

The fall of orange leaves is leaving barren twigs, and the sun is setting earlier now, casting a chilly shadow over the three rivers of Pittsburgh. Happy autumn everyone! Whether fall is your favorite season or your least favorite time of year, there are not many people who do not like Thanksgiving. To you, Thanksgiving could mean a big family dinner, a break from school, an excuse to watch football all day, or if you happen to be a Pilgrim in 1621, a fall harvest celebration at Plymouth Rock.

The story of a joyful, collaborative dinner between Native Americans and Pilgrims is a systemic falsehood. David Silverman, a history professor at George Washington University, writes an accurate account of the scene. “Wampanoag leader Ousamequin reached out to the English at Plymouth and wanted an alliance with them. But it’s not because he was innately friendly. It’s because his people have been decimated by an epidemic disease, and Ousamequin sees the English as an opportunity to fend off his tribal rebels. That’s not the stuff of Thanksgiving pageants. The Thanksgiving myth doesn’t address the deterioration of this relationship culminating in one of the most horrific colonial Indian wars on record, King Philip’s War, and also doesn’t address Wampanoag survival and adaptation over the centuries, which is why they’re still here, despite the odds.”

Recent discussions of the reality of these events have caused many to rightfully reevaluate the meaning behind the Thanksgiving celebration, to understand the oppression hidden behind this holiday.

Although the original Thanksgiving took place before the area Pittsburgh was even a part of colonial America, our city hosted one of the first Thanksgivings and played a huge role in the development of this holiday. Although much lesser-known, nearly 130 years after the feast at Plymouth rock, Pittsburgh had a Thanksgiving of its own, and it is thought to have paved the way for the nationalization of America’s most delicious holiday.

In November of 1758, during the French and Indian War, colonial soldiers were fighting downtown for the control of Pittsburgh. It was considered pivotal to the control of North America, as a strategic location with 3 rivers. The French had occupied the area of the Point up until this time, establishing Fort Duquesne. The British army’s next move, however, was attacking and capturing the fort. Upon hearing this information and realizing they were outnumbered by the might of the Colonial forces, the French decided to flee. They detonated their gunpowder and weapons and set fire to Duquesne the day before British arrival, hoping to cause damage to their enemy’s forces. That strategy did not prove very effective. General John Forbes entered Pittsburgh to find the smoldering ruins of Fort Duquesne with no opposition to their invasion. He and George Washington quickly took over the area with their troops.

General Forbes was so grateful in fact, he declared the following Sunday, November 26, 1758, “a day of public Thanksgiving to Almighty God for our Success.” It later became Pittsburgh’s first Thanksgiving.

Reverend Charles Beatty led this first Thanksgiving service. As many as 5,000 people were known to have attended, including George Washington himself. There were British soldiers, Scottish Highlanders, as well as the Colonists’ Native American allies from the Seneca, and many Colonists who traveled into Pittsburgh. Due to war times and the recent devastation of the town, food was very limited. They likely only had salt pork, hardtack, and possibly a turkey.

During Washington’s first year as the President, he designated November 26 as a day of prayer and giving thanks-the same date selected by General Forbes in Pittsburgh. He spoke very highly of his first Thanksgiving experience. In 1863, Lincoln proclaimed Thanksgiving an American national holiday. In 1941, Congress formalized Thanksgiving as the 4th Thursday of November.

At Allderdice, we celebrate (or do not celebrate) Thanksgiving in different ways. One student says, “Everyone [who celebrates] celebrates in different, but equally valid ways. The diversity of students at Allderdice allows us to explore how different people enjoy the holiday, and lets us compare the similarities in our traditions.”

Pittsburgh did not have the first Thanksgiving. However, General Forbes’ dinner was among the first and likely among the most significant that followed. Whether you are going to celebrate Thanksgiving this week or not, it is interesting to know that this national holiday has a little piece of Pittsburgh in its creation.

Anisha Willis is a senior at Pittsburgh Allderdice High School. She is a Co-Editor-in-Chief, and is a 4 year staff writer for the Foreword. Outside of...