Teachers And Staff Struggle To Address Soaring Failure Rates

Students haven’t had instruction in the Allderdice building in nearly a year because of the ongoing pandemic.

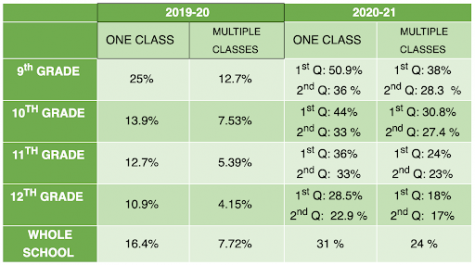

As classes have continued virtually since August, parents and administrators have had concerns about how this shift will impact learning. The first semester has now come to a close, and failure rates obtained by The Foreword have illuminated that Allderdice is in crisis. More than half of freshmen failed at least one class during the first quarter, an 100% increase from the previous school year. Nearly a fourth of all students failed multiple courses during the first semester, a more than 300% increase from 2019-2020. These increases have affected every grade level, speaking to the far-reaching inequities that distance learning presents.

Teachers and staff and staff alike have scrambled to account for the causes of this emergency. “I think the knee-jerk reaction for fourth quarter of last year put us in a hole that we are still trying to dig out of,” said Ms. Davies, 12th Grade Assistant Principal. As the pandemic swiftly closed buildings around the district in March, teachers were not able to fail their students for the remainder of the school year, even if students never attended class online. “That enabled a lot of students to opt out of learning for an entire report period. And then to come back in the fall and tell kids in September you really have to come to class and you really have to do your work, I don’t think a lot of kids believed that because of what happened in the spring,” she added.

Spanish and Portugese teacher Ms. Herrmann agreed with that assertion based on what she has seen in her classroom. “I wonder if some kids still think that maybe they’re going to get a passing grade even without doing things.”

These staggering numbers have been a point of discussion for Allderdice staff, who have worked to implement policies to help students. This process, however, is made more difficult by the lack of immediate action from the school board. The Allderdice instructional cabinet approved the decision to start “What-I-Need (WIN) Wednesdays,” where students have Wednesdays to solely catch up on previous school work. “If we waited for the district to come up with a plan like that, we’d still be waiting,” said Davies. But the cabinet is limited in the policies it can enact to alleviate burdens for students without board approval, which complicates any action.

For the new developments that have been made this school year, rollout has been less than ideal. With multiple, sometimes-contradicting messages coming from the district and the school itself, students and teachers are left unsure what is expected of them. “I think that the school directives can be confusing because they change constantly,” said Herrmann. Multiple weeks after the WIN Wednesday policy went into effect, she was still unclear what work she could and couldn’t assign.

While the failure rates directly represent the impact of virtual learning on student success, it also speaks to the increased pressures and teachers and administrators have faced as a result of the pandemic, making it more difficult for them to effectively serve students. “It’s unfortunate because I think that it’s affecting not only me socially because that’s just who I am, but I think that it’s also affecting kids too who need that social aspect of their lives,” said Mr. Galla, a health and physical education teacher. His class has drastically transitioned as school buildings closed — previously he would engage with students in the Allderdice gym, but now his connections with students are at a minimum, as he grades students by the evidence they submit online of their physical activity. “It affects the kids that have some learning disabilities too because in the gym it’s easy to see everyone moving around and running around—whether you have a learning disability, whether you don’t like P. E., whether you’re tech-savvy or not—and when I see you’re not moving, I can come over and redirect,” he said.

Ms. Herrmann spoke to the challenges she faces teaching to a class without any cameras turned on. “It would make a world of difference to be talking to actual faces,” she said. She can typically hold her students accountable and encourage them in a traditional classroom setting, but online she has found it much more difficult. “I have kids that will never answer, and I call on them, and it’s like they’re not there.”

Administrators have also had to adapt, pivoting to adapt to the new needs of students created in the new learning environment. Assistant principals have taken on the role of tech support, troubleshooting when students experience issues with their computers, coordinating the effort to distribute computers, and even delivering Internet hotspots to the houses of students who didn’t previously have access. “Imagine going from a district with five people in your IT department to now every single kid and teacher has a district device,” said Davies.

While the data raises concerns, it does provide some hope that failure rates will return the previous baseline soon. Rates declined across all grade levels from the first quarter to the second quarter, which some teachers and administrators believed to be the result of students adjusting after better understanding the virtual grading system. Ms. Alessio, 10th Grade Assistant Principal, was pleased to see these improvements. “It’s showing that we’re making strides, that we’re making progress in the right direction. I think students and staff need to be commended for that,” she said.

Senior • Mar 17, 2021 at 10:15 am

This is a very informative article. However I found my experience was almost the opposite. I got good grades in the first semester (As and Bs) but now I’m feeling more depressed and unmotivated as the year has dragged on and nothings changed, and my grades are dropping more in the 3rd quarter (CS and Ds). It will be interesting to see what the overall trend for the year is.