Ghosts Of Pittsburgh Sports Past: The NHL’s Pittsburgh Pirates

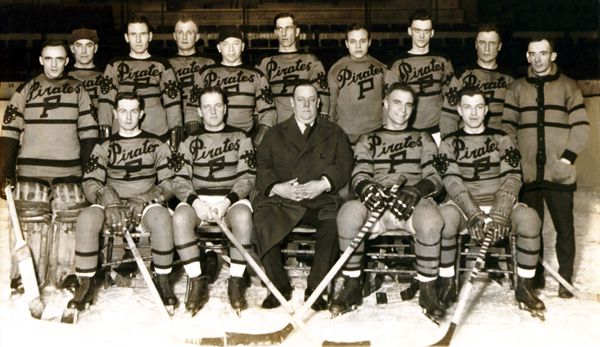

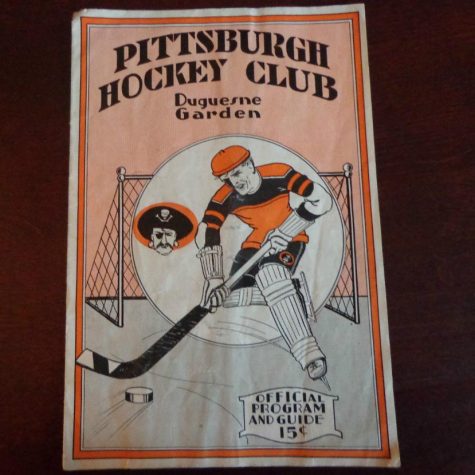

The 1925-26 Pittsburgh Pirates hockey team. | Photo Credit: pittsburghhockey.net

In the 2023 Winter Classic, the Pittsburgh Penguins wore a very historic look: a white jersey featuring a gold P placed prominently above two stripes. The jerseys, taking after a very early era of hockey in Pittsburgh, are an homage to the 1920’s Pittsburgh Pirates, a short-lived team in the very young National Hockey League.

Decades before the Penguins came to town, for five years in the mid to late 1920s, the very young National Hockey League also had a franchise in Pittsburgh, by the name of the Pirates.

The Pirates of the NHL can be traced back to the Pittsburgh Yellow Jackets of the United States Amateur Hockey Association (USAHA), owned by Ray Schooley, who despite his team’s success suffered from financial problems, and was forced to sell to James Callahan, a Pittsburgh-area attorney, and Henry Townsend, president of the Duquesne Gardens.

The USAHA folded after the 1924-25 season, and the Yellow Jackets soon became a part of the National Hockey League after the NHL granted Pittsburgh a franchise.

Callahan decided to rename the team the Pittsburgh Pirates, with permission from Pittsburgh’s baseball club of the same name, and back then, the Pirates name was not something to be taken lightly. Baseball’s Pirates had won the 1925 and 1927 World Series titles, and had been boasting winning seasons for a number of years before the hockey Pirates arrived.

Most of the players from the previous Yellow Jackets signed with the NHL club. The early Pirates, while not successful as a team, had some prominent individual stars. Goaltender Ray Worters and skater Lionel Conacher would end up being inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame. Conacher, nicknamed “The Big Train” and the Pirates made history at the time when Conacher signed a deal worth a salary of $7,500, a record at the time of the deal.

While the deal was large at the time, it was still behind the likes of players like Babe Ruth, who at this same time was making a salary of $52,000 and eventually $70,000. Even back then, hockey players were drastically underpaid in comparison to other sports.

The Pirates’ entry to the league was not a unanimous agreement, however. As the 1925-26 season approached, the league’s Ottawa Senators (not the present-day Ottawa Senators) protested Pittsburgh’s joining of the league.

Ottawa’s official claim was a concern that Pittsburgh’s team, filled for the most part by amateurs, could not effectively compete with the likes of NHL teams, but it’s speculated by some that Ottawa was more secretly worried about their own standing in the league, and keeping up with new NHL teams entering the league in other markets. After failing to gain any support, Ottawa dropped their objection to Pittsburgh joining, and the Pirates were made official.

In October 1925, the Pirates named James Ogilvie Cleghorn as coach.

Known as a snappy dresser, Cleghorn was the younger brother of Hall of Famer Sprague Cleghorn, and he himself had a lengthy playing career, appearing in action for the New York Wanderers, Renfrew Creamery Kings, Montreal Wanderers, and Montreal Canadiens over a decade and a half.

Nicknamed “Odie”, Cleghorn ended up changing the game of hockey in a massive way. He had the revolutionary coaching style of changing his players on the fly. Cleghorn’s idea of changing on the fly was eventually copied by the rest of the league, and today is so ingrained in the way hockey is played it’s considered an afterthought by many.

Cleghorn also had the mind to play his team as set forward lines, rather than using his star players to their absolute breaking point and burning them out.

But if he needed to, Cleghorn was always ready to get on the ice and play for his team himself. Cleghorn played in 17 games as a substitute forward for the Pirates in their first season, scoring 2 goals and adding an assist.

Imagine Mike Sullivan hopping over the boards and joining the ice with his team. Impossible, right? It’s something that would boggle the mind of any NHL fan today.

The Pirates began their first season, 1925-26, in Boston on Thanksgiving night, stunning the Bruins with a 2-1 win thanks to goals by Lionel Conacher, the team’s captain, and Harold Darragh, and 26 saves from the goaltender Worters.

The Pirates were able to jump out to a fast start, going 5-2-0 in their first 7 games, impressing the league and media alike. But, their momentum was not to last. An 0-6-1 slump would plummet Pittsburgh in the standings. Their slump also led to a downturn in fan attendance, something that the Pirates would continue to struggle with.

After some ups and downs in the season, the Pirates went on a 7-1-0 run to close out the season and push their way to the playoffs with a final record of 19-16-1, set to face off against the Montreal Maroons.

In the early days of the NHL, the winner of a series was determined by the total number of goals scored, not by the actual winner of the game itself.

The Maroons had bested Pittsburgh 3-1 in the first game, and settled for a 3-3 tie in the second and last game of the series, overall beating the Pirates 6-4. It was reported that 7,000 fans had packed the Duquesne Garden in Pittsburgh, and that thousands more had to be turned away for lack of space.

The following season, speculation had swarmed around the star Conacher, who reported to training camp a week and a half late, and was fined upon arrival.

Cleghorn was very confident about his club, and had claimed that he planned on adding two more amazing players to their roster, but nothing would ever materialize.

The Pirates had almost an exact replica of their previous season, with a fast start out of the gate only to be thwarted by an extended losing streak that sent the Pirates to the basement of their division (a place today’s baseball Pirates are unfortunately very familiar with).

But most notable in this season was the Pirates’ decision to trade Conacher. After continued tension, Conacher was dealt to the New York Americans in December of 1926.

The trade was lopsided, with Pittsburgh only receiving 32 year old defenseman Charlie Langlois (Conacher was 25), and $2000 in cash.

Conacher would go on to play over a decade more, while Langlois’s career would end in 1927-28.

That unsuccessful deal would be the theme of the season, as the Pirates continued to fall, and things began to get rocky. Part owner Henry Townsend died, disrupting Pittsburgh’s management, and as the Pirates averaged just around 2,000 fans a game, questions about their future began to persist.

Rumors of the team’s potential move to Philadelphia began to spread, and even though the NHL would halt any attempt to move the Pirates out of Pittsburgh, concerns over their future were still rising. Cleveland also rose as a potential new home for the club.

Even with the distraction of potential relocation, the Pirates made the playoffs in 1928, and they were even supposed to host a playoff game, but the league moved their game against the Rangers to New York because Madison Square Garden could fit almost five times the people that the Duquesne Gardens could.

The Pirates would lose to the Rangers in the playoffs (still in the two-game, total-goal format) by a final score of 6-4.

It’s in 1928 when things got crazy…

The Duquesne Gardens’ size continued to be a talking point as the Pirates were sold from the Townsends into new hands.

Retired lightweight boxing champion Benny Leonard appeared to be the owner of the club, serving as the face of the team.

But the team was actually owned by William “Big Bill” Dwyer, a gangster during the Prohibition era in the United States who got rich off of bootlegging. He used that money to dive into the sports industry, including secretly buying the Pirates.

Dwyer’s life is a rollercoaster, but to quickly sum it up, Dwyer was one of the top bootleggers in the early years of Prohibition. Working at a dockyard, Dwyer had access to a vast amount of supply trucks and garages.

Dwyer ran a network of garages that were able to hold many supply trucks and were only accessible by Dwyer and a select few via secret doors and passageways. Dwyer was a high ranking fellow, getting protection through James J. Hines, a member of the Democratic Party and a powerful leader of the notorious Tammany Hall, as well as members of the New York Police Department and the Coast Guard.

Dwyer was arrested in 1925 for attempted bribery, sentenced to two years in prison but was released halfway through on good behavior. After that, he began to enter other industries, including sports.

The Dwyer-Leonard era was rocky, and the Pirates were unable to come to terms with several of their players, including goalie Ray Worters.

Leonard committed to keeping the team competitive and in Pittsburgh, but that would prove difficult as the Pirates failed to make the playoffs that season and relocation threats still loomed large.

Entering the 1929-30 season, Odie Cleghorn was out as coach, and the team rebranded to new black and orange colors (which is some wacky foreshadowing).

The Pirates’ spiral continued to worsen, as Pittsburgh posted a 5-36-3 record. The stock market crash in 1929 and the Great Depression only contributed to the Pirates eventual death. After an increase in attendance the season prior, attendance numbers once again plummeted, and the Duquesne Gardens was no longer a viable arena for the team to play in.

The Philadelphia move became more and more likely, and at the 1930 NHL Board of Governors meeting, Leonard officially moved the team to Philadelphia, where they were renamed the Philadelphia Quakers.

Leonard’s original intention was to keep the team in Philly until a new arena could be built in Pittsburgh for the team to play in, despite him telling fans in Philly that they were staying put there. Ironically however, arena issues would contribute to the Quakers demise as well.

The Quakers, miraculously, posted an even worse record than the Pirates’ last season, going 4-36-4 in their one and only season in Philly.

As the Great Depression continued to take its toll on, well, everything, the Quakers temporarily ceased operations as they awaited a new arena in either Philly or Pittsburgh. For years the organization sat dormant, waiting, but no arena would ever come to fruition.

In 1936, the franchise was officially shut down.

The Quakers’ fold was one of several around the NHL during this time, and the effects of the economy at the time left the NHL with only 6 teams. The NHL would play as a 6 team league all the way until 1967, when they expanded to double league size.

Among the 1967 expansion teams were both the Philadelphia Flyers and the Pittsburgh Penguins.

Check out more of the Ghosts Of Pittsburgh Sports Past series:

Alex Kiger is a Senior at Pittsburgh Allderdice High School. He is the Sports Editor at The Foreword from 2021 to 2023. In his free time he can often be...